“Roma Ai Tempi del Coronavirus”

“I boil them. I take them home at the end of the day and when I am making my dinner I boil a pot of water and I put them in. Then I set them to dry. Yesterday a fake coin floated to the surface ! Yah ! I don’t know what that was !”

My Nigerian refugee friend Simon smiled ruefully, and extended his cap to a lady who was wiping her mouth with a tissue as she stepped from the pastry store. “Grazie, signora” he said, as a golden 10 cent coin fell into it. (“That was real !” said Simon. “She is a reliable signora”.)

“Simon, are you worried about Coronavirus, catching it yourself ?” I knew that Simon took a bus from Pomezia, 30 kilometers away, to Rome’s Termini station and then the 75 bus to the pastry store where he stood each day, with his cap out, hoping for the handouts that sustained him.

“Yes, I am worried, but no I am not worried because better here than Nigeria. Oh my God.” And Simon extended his hat again as I stepped into the bar pasticceria.

STOP ABBRACCI ! screams in bold letters the newspaper front page I find on the counter. STOP HUGGING ! More admonitions follow, many involving the necessity of maintaining a distance from your fellow man.

Here, at my Roman neighborhood pastry store cafe, where we patrons generally crush around the bar counter into a single mass of speedy-pleasure-consumption, we now are allowed to consume only at small, unbalanced tables, each placed precisely one meter from one another, with one customer per table. The owner, who looks determined, and is herself holding a cappuccino, directs traffic. “Signora Bruna, li.” She points to a corner table. “Signor Flavio, ha finito ? Bene. Puo’ liberare velocemente, per piacere ?” (“Have you finished, Mr Flavio ? Will you please free your table ?”) As the habit of downing the morning espresso, with or without a pastry, is not generally a lingering one, there is continuous rising and settling down, a musical chairs game as each patron, under the owner’s gaze, liberates his or her seat for the next customer, often trying not to handle the stool, so pushing away at it with paper napkins.

Many of the bar’s patrons, observing this unfamiliar scene, opt for the otherwise unheard of paper cup and stand apart from others and in the pastry display area, gazing at the usual array of offerings as they consume their caffè.

The familiar pastries are all there — maritozzi con panna, plump brioches split in half, with a cascade of whipped cream that can be barely contained. Occhio di bue, round, powder sugar-dusted, hand-sized biscuits with a shiny central eye of apricot jam. Latticed crostatatine, with raspberry and bitter cherry jam, are lined up, and then a variety of biscuits. A bright birthday cake adorned with candied daises and roses, and a cursive “Auguri Maria, 90 !”

Coffee consumed, I rise and free a seat for my market lady, an old friend who has shelled for me one kilo of fava beans, ready to collect when I pass by the market later.

Because now I am heading down the hill to Piazza Navona to meet a hotel owner, who wants to discuss the upcoming season, a topic that makes her feel “destroyed”. As I leave the pastry store, I wish Simon a pleasant day and proceed to the 75 bus stop.

My father always said that the reason Romans take such pleasure in the preposterous is that they are descendants of the Etruscans, and that behind the half-moon smile of Etruscan representations is a laugh always ready to break. One of the recommendations in Emergenza Coronavirus is that we not touch surfaces in public places. The agility required to stay upright without holding onto bars and straps on the 75 bronco causes much neighborhood muttering — but is also recognized as humorously preposterous.

The 75 is legendary for lurching, for slamming on its breaks, for accelerating without warning and activating, then jarring every bone and tendon in your body. I had waited for close to 40 minutes for the 75, reading my Messaggero newspaper cover to cover, and studying the number of daily diagnosed cases in each region, the number of hospitalizations, the number of hospitalizations in intensive care, the number of deaths, and finally, in its own category, the number of recovered, each of which is of course treated as a celebration. While the 44 bus had sailed past three times, each bus close to empty, the 75 had through the sloth of its pace brought about 30 of us waiting passengers together. By and large we were all eyeing one another, attempting to keep something like one meter apart. But of course when the 75 lumbered to a stop, instinct and habit overtook us all, and we clambered on as one mob, a lame and very overweight lady holding heavily on to the railing while a woman behind gave her a helpful push from the back. Once aboard, the group attempted to disperse, again eying one another and considering how to maintain one meter. One passenger hovered near the driver, two perched on either side of the ticket machine. Two priests sat together, both in facial masks. The elderly lame lady was given a seat but no one would sit next to her. There were many untouched seats, with half the passengers standing, including two junior year abroad Americans who spoke loudly and tearfully about their program being cancelled, requiring them immediately to return home to Arkansas. “It sucks so bad”, said one. “This was the most awesome thing I ever did, and I have to go away” lamented the other.

The 75 took one of its characteristic rolls, and all of us who were standing instinctively reached for a bar or strap, but then many of us stopped and caught ourselves, the newspapers’ admonition etched in our heads not to touch the ultra germy surfaces of public transport. I fell somewhat heavily into a teenager, who was absorbed in the music that came through his headphones, and who looked up startled — but gave me a small sweet smile and said “non si preoccupi signora, tutto bene” (“don’t worry, Signora, it’s fine.”)

There was laughter in the bus as we realized that none of us who were standing were hanging on, and we all had fallen into someone else or against another surface. “Tutto bene ?” barked the driver, who turned around to observe his passengers. “Tutto bene”, he declared, and “Si parte”. We all replanted our feet, teetering close to but not touching rails and hand grips.

Starting tomorrow, when they are dry and I can put them on, my defense from Corononavirus will be my mother’s freshly washed, 1952 buttoned gloves, which come all the way up to my elbows. I am already strengthened I hope by my curiosity, which surely is an immune system booster. I also carry a small, precious container of hand sanitizer that I share with friends who are out of it more than I actually use it myself. In my handbag is a miniature bottle of olive oil, which I rub often into hands chapped by continuous washings.

I circulate fascinated by the city that has been home most of my life, and watch the familiarity and the unfamiliarity, as Romans come to terms with changed circumstances and find their own way of accommodating a Coronavirus that for all that we know, and with just a speck of exception in our six local cases, is mostly hundreds of kilometers away. The present major Italian epicenter is in Lombardy’s Lodi, 545 kilometers away, 340 miles or, as a classicist friend kindly told me, 370 ancient Roman miles.

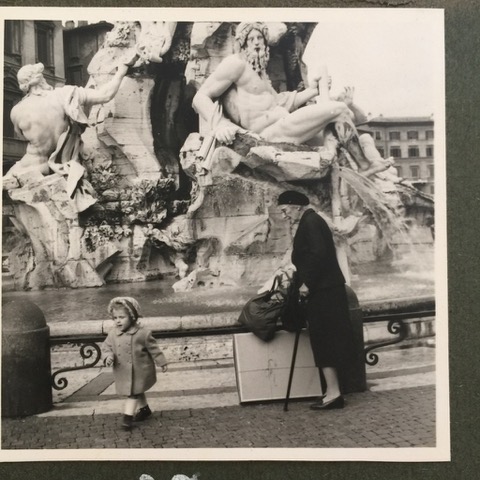

“Where is this Tsunami that is destroying our business ?”, barks out my friend, the hotelier, as she greets me in front of the Fountain of the Four Rivers, and we set off for an aperitivo and conversation in her office. Then she looks at me. “Why, I suppose this square” — and she motions to the magnificent oval piazza, close to devoid of sightseers – “must have looked like this when you were a little girl, a million years ago ?” She pauses, and muses, pushing her sunglasses back to gaze at the bright, beautiful, empty space : “Roma Ai Tempi del Coronavirus”, she says. Rome at the time of Coronavirus.

Marjorie Shaw

www.insidersitaly.com

March 5 2020

Meet Marjorie

Insider’s Italy is an experienced family business that draws on my family’s four generations of life in Italy. I personally plan your travels. It is my great joy to share with you my family’s hundred-year-plus archive of Italian delights, discoveries and special friends.