The Insider’s Cilento

When I travelled onto the Cilento Coast last week, I was in an Italy that I thought had disappeared. It felt very much like one imagines falling into a time warp; and I puzzled why it had it taken me decades to explore with any thoroughness this unique portion of the Campania region?

When I travelled onto the Cilento Coast last week, I was in an Italy that I thought had disappeared. It felt very much like one imagines falling into a time warp; and I puzzled why it had it taken me decades to explore with any thoroughness this unique portion of the Campania region?

While no more than an hour from the southern tip of the Amalfi coast, it is like another region altogether, although it is not.

Cilento’s northern perimeter is Paestum, 90 minutes south of Naples.

The area extends both several hours down the coast and the same distance inland.

The combined Cilento, Vallo di Diano and Alburni National Parks — which contain many historic villages and places of cultural and artistic interest — are Italy’s second largest protected area, second only to the Gran Sasso in the Abruzzi.

The providence in designating this area forbidden for overbuilding is to some large extent what has saved its exceptional natural beauty.

There are no cruise boats, no large hotels, no tour buses.

The coastal villages that 1950s and 1960s Amalfi Coast visitors (over)discovered are, in contrast, still quiet here. Fishing is still important, and so is the quality of life.

Emigration emptied many of Cilento’s villages, but today no village feels empty. Rather, there is a sense of self-contained prosperity which is not tourism dependent. There are not the sprawling modern outskirts that circle many Italian cities.

Much of the Mediterranean enjoys great diversity of landscapes, but in Italy there are few areas that remain so uncontaminated, with very rich flora and a low human presence which has allowed the preservation and protection of natural environments and biodiversity.

There are no guidebooks or other resources that document the Cilento. Americans are rare and most residents don’t speak English. You will need our friends and our guides to open doors for you here, and their enthusiasm will add immeasurably to your experience.

Towns, especially in the summer months, close for lunch. You hear a pin drop for the hours until the village awakens, opens its shutters and resumes the business of the day.

Roofs are terracotta tile, providing an aesthetic uniformity.

Cilento is not on the tourist radar, even for Italians, this despite having a stunning number of White Flag beaches — those designated of highest European standards.

Cilento offers wonderful opportunities for hiking, cycling and riding, as well as foraging for and learning about wild herbs and traditional agricultural practices in some of Italy’s wildest and most arrestingly beautiful scenery.

Which brings me to my point, one made to me at lunch last month at a trattoria run by three generations. The nonna approached, perhaps aged 90, and asked us how we were enjoying the homemade fusilli, made by her experienced hands. She said: “I carried bags of grain on my head for so many decades. We all did. We worked the land. Those were good years, happy years. So much hard work, but we had everything, everything, and we had the family. And we had the land.”

Her grand-daughter Raffaella, who runs the restaurant, came to her side. Nonna hugged her grand-daughter and moved slowly off to the kitchen to continue her handiwork with the fusilli, stopping to greet her teenage great granddaughter who was at a table and just finishing her own plate of fusilli.

In our days of exploring Cilento we met kind, intelligent and generous local people with time to talk. We saw acute environmental sensitivity and keen entrepreneurship. We found enormous pride in the place where they were born or where they chose to live. We found a strong attachment to the land — to the still flourishing olive trees that so often here are far more than 1,000 years old; to the vineyards; to the traditional ways of making sheep, goat and cow cheeses; curing pork products, and cooking.

Remembering always that Amalfi and Positano (in peak season, 100% Instagram-saturated and 100% dominated by tourism) are just a sniffle away, what I saw in Cilento was this: a place and a people that are quite happy to remain out of the mass tourism program.

Sustainability is embraced as an unbroken tradition, not as a marketing slogan.

It was interesting reading recent on-line Italian responses to a recent NYT piece on “Undiscovered Cilento”.

One Cilento reader commented “Excellent, let’s leave it undiscovered” and another wrote: «Please : we don’t need tourist crowds. Discover Arizona or Iowa.”

And a third: “Please don’t try to make us into Positano.” Hundreds of Italian “likes” followed all these remarks.

Travelers who visit Cilento on an Insider’s Italy trip have an opportunity not afforded in much of Italy: their presence supports traditional industries and artisans who do not see many tourists. These artisans’ lives are devoted to ensuring that Cilento’s traditional industries continue but they personally are equally committed to ensuring that Cilento remains unexploited.

Cilento offers blue grottoes, dramatic river gorges, waterfalls, remarkable caves—some of the most exciting and extensive in Europe—as well as watchtowers, magnificent wildflowers (especially orchids), broad biodiversity in birds, land animals and plants, and… anchovies (among other fish species).

Marina di Pisciotta, one of the many pretty villages, is locally famous for keeping alive its centuries-old fishing techniques, using methods that were originally brought here by the ancient Greeks. To find a functional fisherman on the Amalfi coast is increasingly difficult, but here fishermen continue to go out, using the moon and the stars to determine where anchovies will be. Their boats are unique, perhaps the last of their kind in Italy, as are their nets. And as for the anchovies, it is close to impossible to do justice to what they taste like, fresh, barely cooked, sweet and intense, a flavor hard to forget.

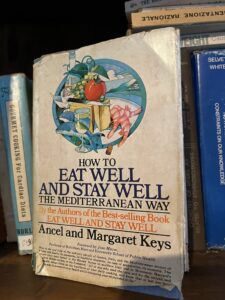

These anchovies are a central part of the “Mediterranean Diet”, a phrase first penned by American Ancel Keys, and recognized since 2010 on the List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. From 1963 – 1998 biologists Margaret and Ancel Keys lived in Pioppi (wintertime population 200) and investigated why the Cilento had so many fewer cardiovascular problems than elsewhere.

The Keyes’ pioneering and broad lateral study led them to conjecture that Pioppi’s diet, combined with lifestyle, contributed to the unusual longevity and persistent good health of the population.

The Cilento Mediterranean diet’s focus is largely vegetarian with however anchovies a focus, together with seasonal fruit, vegetables, olive oil, grains, wines and local sheep and goat cheeses.

All of these products are today as deeply, intensely flavorful as they were in the early years of the Keyes’ study: and a large part of the joy of exploring the Cilento Coast is the immersion, with an introduction by the artisans themselves, into its culture of superb local foods. We were enchanted by ingredients and dishes specific only to this area including the fusillo di Felitto, the Salella olive, Prignano Cilento fig, Cicerale chickpea, cacioricotta cheese, pummarola gialla tomato.

What we found, as we explored the valleys and the coastline of Cilento, was an awakening: food artisans who are operating on a very small scale, and yet are not confined at all by the apparent remoteness of this area.

What we found, as we explored the valleys and the coastline of Cilento, was an awakening: food artisans who are operating on a very small scale, and yet are not confined at all by the apparent remoteness of this area.

They have inherited tradition, they have studied what Italians are doing in other regions, and they are able to nurture and shape, in this clean, unadulterated land, excellent products that speak intensely of their terroir.

There are unexpected delights here too: the museum of local hero, Joe Petrosino, a pioneer in the fight against New York organized crime century, and ultimately murdered in Italy by the Mafia in 1909.

This celebrated police chief’s story is narrated in a remarkable and quite dramatic oral history of “Zio Jo” by his septuagenarian great-nephew.

And then there is the Certosa di Padula, which is a feast unto itself.

The second largest charter house in Italy and constructed by the Carthusian order in 1306 with additions over 450 years, it incorporates the biggest courtyard in the world; exquisitely frescoed baroque chapels with rich intarsia floors, inlaid wooden walls and choir stalls; a vast and magnificently tiled kitchen, and beautiful library.. in total, 320 rooms!

In 1998, it became a UNESCO World Heritage Site — as in fact did the entire Parco Nazionale del Cilento e Vallo di Diano as well as the archeological site of Paestum.

As for Paestum.. when the beauty of this area, and the swimming in azure blue waters, becomes too euphoric, you can examine man-made splendor at Paestum, at the northern border of Cilento.

Paestum lifts and speaks to my spirit in a way that few other places can. I think you will feel the same. Paestum offers unearthly enchantment, and each time I am there I cannot believe that such a place exists.

One of my favorite destinations in all of Italy, Paestum offers three Greek temples ringed by a majestic Roman wall circuit — and outside of it, fields of vegetables including, in season, what I think are the best artichokes in Italy.

Nearby are traditional buffalo farms that produce a mozzarella that makes me cry each time I try it here.

I send all our clients to a buffalo dairy farm run by Antonio Palmieri. Last month I found him in the new bakery he has installed on the property: alongside the mozzarella sales area, the cafe’ and the wonderful restaurant.

As ever, he offered an exceptionally friendly greeting.

“Margherita, hello, and welcome back. So nice to see you again. You see I am here too. You know what I do, I have told you before. I am here to watch and listen, l circulate as a guest. I want to watch all the operations, ensure that there is a balance in everything, that we maintain first and foremost the highest standard of life for the animals, and then for everyone and everything else. ”

I bought 300 grams of focaccia with cherry tomatoes and listened as he continued.

“I am pleased with these breads, made with exceptional organic wheats. That’s another anomaly around here. But at this point the locals are used to me, the local madman, or visionary, or whatever it is that I am. You remember that they said when I began this farm : ‘you can never do this. You cannot create an organic dairy’. They said: ‘you cannot make a closed circle, growing all the forage yourself’. But I made mozzarella in the way I wanted to, with the well-being of the buffalo at the center.

Then they said: ‘you cannot make plain yogurt. You must make flavored yogurt’. But pure, plain yogurt, the purest expression of the buffalo’s milk: that is what I wanted to do. And I did. ”

Everyone I know, on the Amalfi coast and in Naples, makes the trek as often as they can to Vannulo, first for mozzarella and then for the sublime yogurt and puddings and other buffalo milk products, and now for the bread.

Signor Palmieri does not sell any of his products anyplace off his own property. “I want to keep the circle tight”, he said. And “can I offer you a buffalo ice cream?” And, here, I must add that Antonio Palmieri’s flavored yogurts, custards and gelato are as divine as his plain yogurt.

My friend Giocondo from Furore, on the Amalfi coast, is also just discovering Cilento now.

He calls it “un patrimonio umano unico.”

A unique human patrimony.

This is one of the few places in Italy where families still come together for Sunday lunches, where children run and play through the streets of ancient towns, where older residents sit and chat for hours, where the piazza fills regularly for the aperitivo.

It is the Italy where I grew up, where olive trees were cherished and passed from one family generation to the next.

It was the Italy I thought that I would never find again.

But in the Cilento, I have.

Meet Marjorie

Insider’s Italy is an experienced family business that draws on my family’s four generations of life in Italy. I personally plan your travels. It is my great joy to share with you my family’s hundred-year-plus archive of Italian delights, discoveries and special friends.